Introduction to Scripting

Congratulations, you finally arrived at one of the most technical parts of the manual. Keep that in mind in case you get lost.

The UPBGE game engine was once famous for letting you create a full game without touching a single piece of code. Although this may sound attractive, it also leads to a very limited game-making experience. Logic bricks, as presented in Logic Bricks chapter, are very handy for quick prototyping. However, once you need to access advanced resources, external libraries and devices, or simply optimize your application, a programming language becomes your new best friend.

Through the use of a scripting language called Python, the game engine (as UPBGE itself) is fully extensible. This programming language is easy to learn, although extremely powerful. Be aware, though, that you will not find a complete guide to learning Python here. There are plenty of resources online and offline that will serve you better. However, even if you are not inclined to study Python deeply now, sooner or later you will find yourself struggling with script files. So, it’s important to know what you are dealing with.

Note

Yes, You Can

For those experienced Python programmers (or for those catching up with the reference learning material), always remember: if you can do something with Python, chances are, you can do it in the game engine.

After the brief overview in the Python basics, we will explain how to apply your knowledge of Python inside the game engine. You’ll also learn how to access the Python methods, properties, and objects you’ll be using.

Why Script When You Can Logic Brick It?

We can compare logic bricks with real bricks. On the one hand, we have strong elements on which to build our system, but, on the other hand, we have a system as flexible as a blind wall.

There are many occasions when the same effect can be achieved in different ways. Different phases of the production may also require varied workflows. The reason for picking a particular method is often personal. Nevertheless, we present here a few arguments that may convince you to crack a good Python book and start learning more about it:

Sane replacement for large-scale logic-bricked objects.

Better handling of multiple objects.

Access to UPBGE’s advanced features.

Use features that are not part of UPBGE.

Keep track of your changes with a version control system.

Debug your game while it runs.

Note

Logic Brick, the Necessary Good

You can’t ever get away from logic bricks. Even when using Python exclusively for your game, you will need to invoke the scripts from a Python controller. The ideal is to find the balance that fits your project.

Sane Replacement for Large-Scale Logic-Bricked Objects

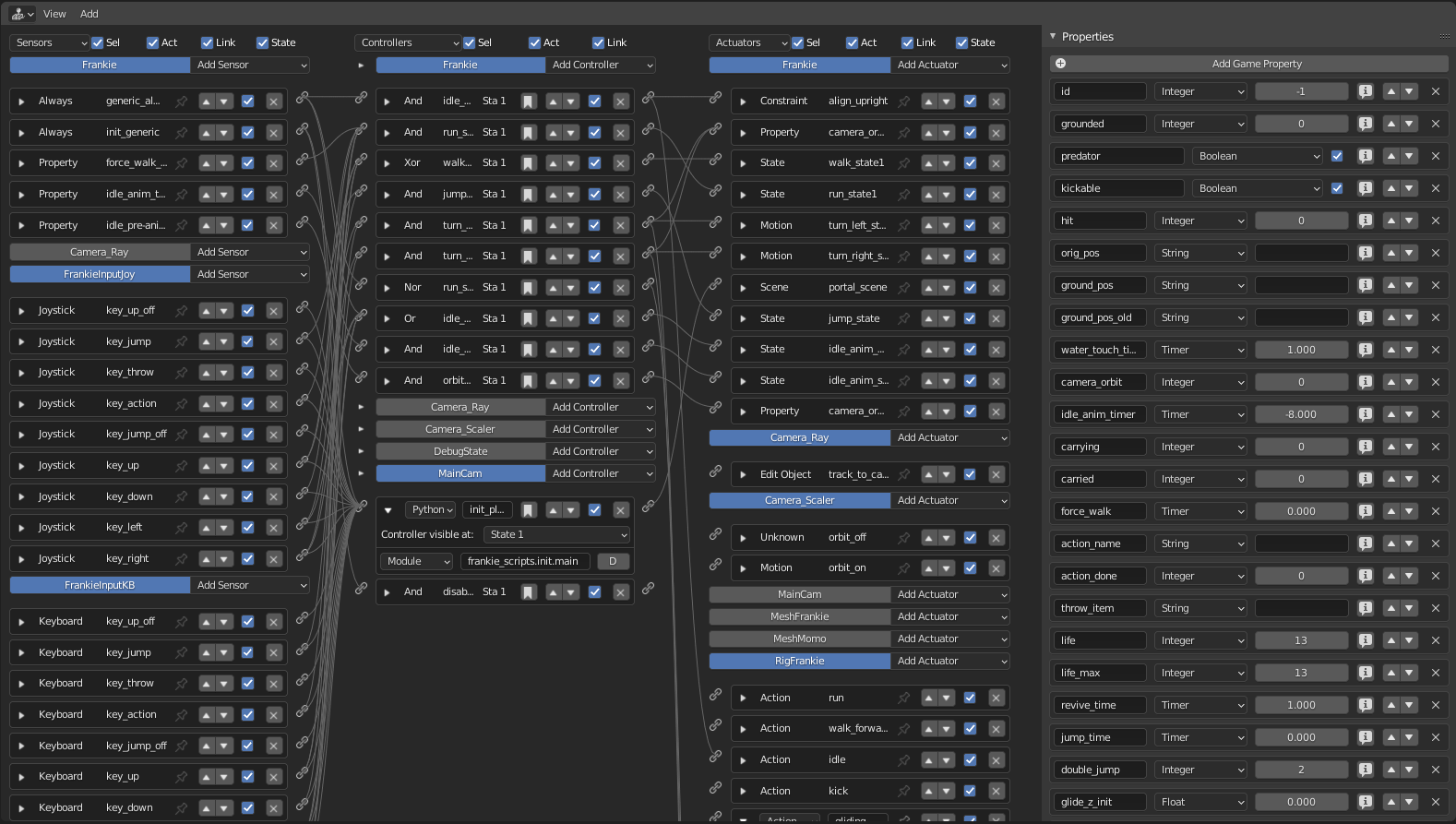

It’s always good to have an excuse to show an image in a programming chapter, and here it is. In the next pìcture you see the logic bricks for Frankie, the main character of the open game Yo Frankie!

Chapagetti

This system is well organized: different actions belong to different states and sensors; controllers and actuators are properly named. Nevertheless, it’s not hard to lose yourself trying to understand which sensor connects to which controller. One of the reasons for such a complex project to rely on logic bricks is because Yo Frankie! serves as a didactic project for artists wanting to start with the game engine. Anyone with a little programming experience can take the files and expand the game freely. (Have you tried it yet?)

However, you often aim for performance and workflow. Having everything centralized in a single script file can save you a lot of time.

Another important aspect while working is to document your project. It’s easy to open a file only a few months old and find yourself completely lost. Script files, on the other hand, are naturally structured to be self-documented. To document logic bricks, you need to rely on text files inside or outside your Blender files (and neat image diagrams). It’s definitively not as handy as inline comments along your code. (Code diagrams can still be useful, but that’s a different topic.)

Better Handling of Multiple Objects

Big projects lead to multiple files, this is an inevitable truth. Even when you use external linking and libraries, it’s crucial to optimize the time spent in changing multiple sets at once. This is one of the weaknesses of logic bricks, they make it hard to automatically change a big range of elements at the same time.

If you need to change a property name or initial value of an object, you will need to repeat that change in other instances of the same. We have ways to make it easier by using copy and paste of logic bricks/properties between objects or even through logic sharing. Nevertheless, you will still have to update all the Property sensors, controllers, and actuators that may rely on the old value. That’s especially true for objects with logic bricks across them, as we saw, the game engine allows you to link logic bricks from different objects. However, self-contained objects/logic bricks are easier to work with (and with less spaghetti).

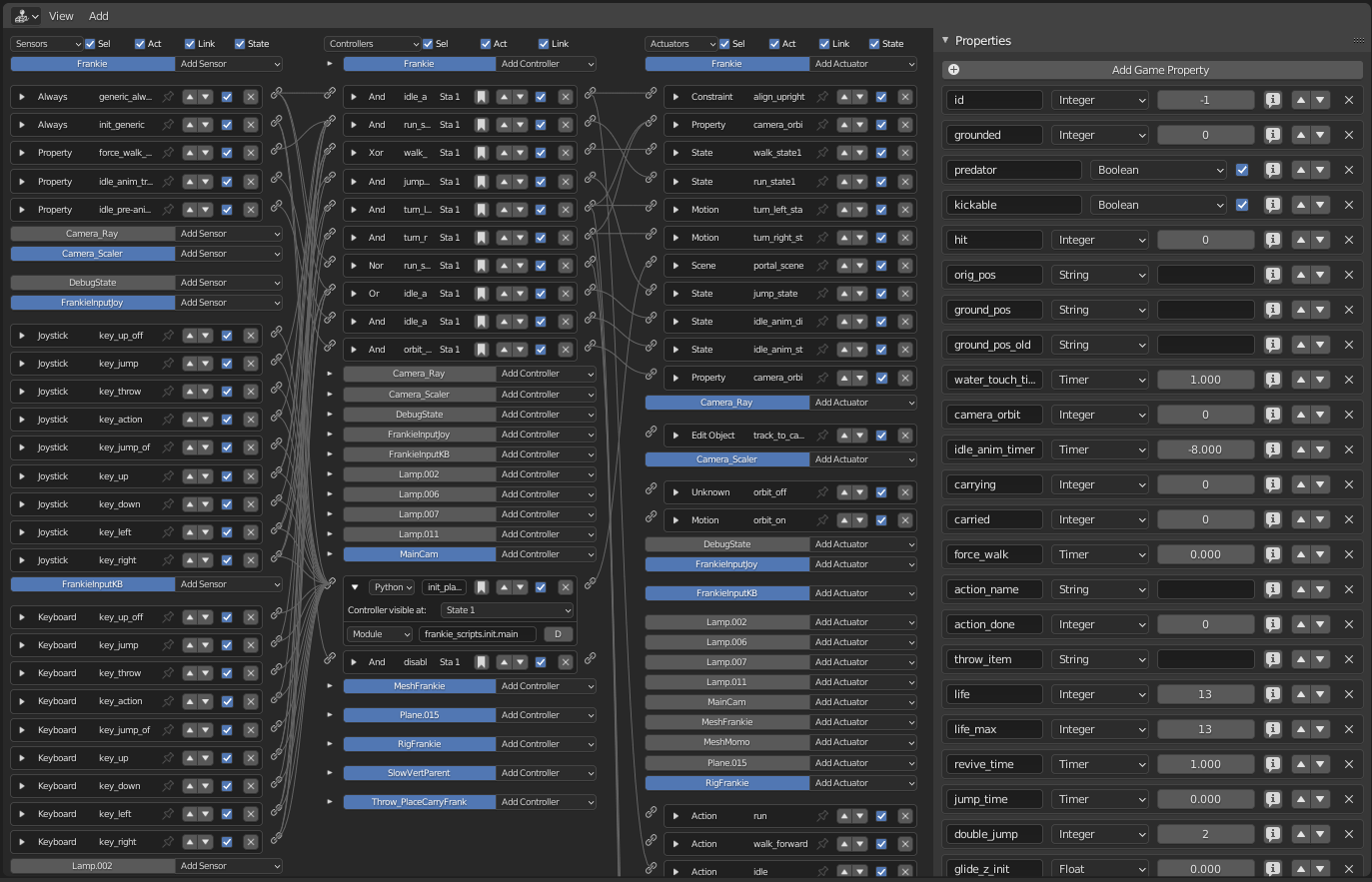

If you thought that before picture was a mess, try to make sense of next picture. Here we have the logic bricks of Frankie, plus the objects that have logic bricks connected to it. As you recall, you can restrict the visible logics through the Show Panel option, but this illustrates how difficult it is to get a global view of your system.

Spaghetti

Once you start to work with scripts, you will see how easy it is to assume control over all your scene elements in a global way. It will give you lots of benefits in the long run.

Access to UPBGE’s Advanced Features

You will be happy to know that the game engine has a powerful set of features beyond those found in the logic brick’s interface. Also, almost all the functionality found in the logic bricks can be accomplished through an equivalent method of the game engine API (which will be covered in the section “Using the Game Engine API - Application Programming Interface”). The API ranges from tasks that could be performed with logic bricks, such as to change a property in a sensor or to completely remove an object from the game, all the way to functionality not available otherwise, such as playing videos and network connection.

There are a few reasons for not having all the methods accessible through logic bricks. First, a graphic interface is very limited for complex coding. You may end up with a slow system that is far from optimized. Second, having methods independent from the interface allows it to be expanded more easily and constantly (from a development point of view). Some advanced features, such as mirroring system, dynamic load of meshes, OpenGL calls, and custom constraints would hardly fit in the current game engine interface. They would probably end up not being implemented because of the amount of extra work required. Other things you will find in the game engine built-in methods are: make screenshots; change world settings (gravity, logic tic rates); access the returned data from sensors (pressed keys, mouse position); change object properties (camera lens, light colors, object mass); and many others we will cover in the course of this chapter.

Use Features That Are Not Part of UPBGE

No man is an island. No game is an island either (except Monkey Island). And the easiest way to integrate your UPBGE game with the exterior world is with Python. If you want to use external devices to control the game input or to tie external applications to your game, you may find Python suitable for that task.

Here are some examples that showcase what can be done with Python external libraries:

Grab data off the Internet for game score.

Control your game with a Nintendo Wiimote controller.

Combine Head-tracking and immersive displays for augmented reality.

Those possibilities go with the previous statement that almost everything that you can do with Python, you can do in the game engine. And since Python can be used with modules written in other languages (properly wrapped), you can virtually use any application as a basis for your system.

Note

Cross-Platform, Yes; Cross-Version, Not

To use external libraries, you must know the Python version they were built against. The Python library you are using must be compatible with the Python version that comes with your UPBGE. It’s also valuable to check how often the library is updated and if it will be maintained in the future.

Keep Track of Your Changes with a Version Control System

If you take a Blender file in two different moments of your production, you will have a hard time finding what has changed between them. This is because UPBGE/Blender’s native file format is a binary type. Binary files are written in a way that you can’t get to them directly, they are designed to be accessed by programs and not by human beings.

Scripts, on the other hand, are plain text files. You can open a script in any text editor and immediately see the differences between two similar files. Finding those differences are vital to going forward and backward with your experimentations during work. Actually, if you don’t want to check for differences manually, you may want to consider using external script files with a version control system such as Git, SVN, Mercury, or CVN.

Note

And the Catch Is …

This works only for scripts maintained outside UPBGE. This is one of the strong reasons to prefer Python Module controllers as opposed to Python Script controllers.

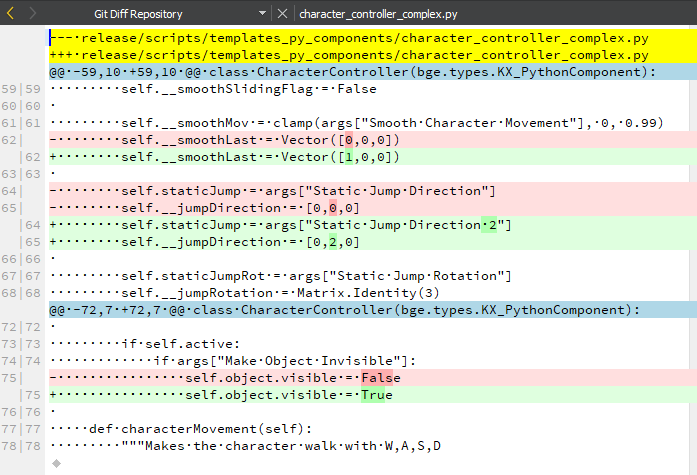

A version control system allows you to move between working versions of your project files. It makes it relatively safe to experiment with different methods in a destructive way. In other words, it’s a system to protect you from yourself. In next image, you can see an application of this. Someone changed the script file online while we were working locally on it. Instead of manually tracking down the differences, we could use a tool to merge both changes into a new file and commit it.

Git diff

Debug Your Game While It Runs

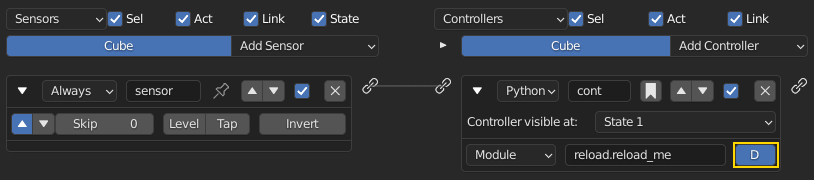

Interpreted languages (also known as scripting languages) are slower than compiled code. Therefore, to speed up their performance they are precompiled and cached the first time they run (when you launch your game). This is not mandatory, though, and if you are using external Python scripts (instead of those created inside UPBGE), you can use the debugging button to have them reloaded every time they are called.

In next figure, we have the reload.reload_me module that will be reloaded every frame. That way you can dynamically change the content of your scripts, variables, and functions without having to restart the game. Try it yourself: download the example 001_reloadme.zip to your computer, extract it and launch debug_python.blend. Play your game, and you will see a spinning cube. The speed of the cube is controlled by the 14th line of the file reload.py, found in the same folder.

# edit the speed value and you will see the rotation changing

# (try with values from 0.01 to 0.05)

speed = 0.025

Debugging button at Python Module controller

Without closing UPBGE or even stopping your game, open the file script.py in a text editor, change this line to 0.05, for example, and save it. You will see the speed changing immediately. Your game is literally being updated at runtime, and you can change any module that’s been called with the debug option on.

Note

Turn It Off When You Leave

Remember to turn debugging off when you are done with this script. Reloading the script every frame can drastically reduce your performance.

So What Exactly Is Python?

Now that you are aware of all the benefits of using Python, it’s time to understand what Python is. Once again, we can’t go over all the aspects of the language here. Nevertheless, a general overview is still desirable to help you understand the examples presented in this book.

To study your scripts, you must be aware of the following aspects:

Flexible data types;

Indentation;

OOP, Object-Oriented Programming.

Flexible Data Types

Whenever you write a program, you have to use variables to store changing values at runtime. Unlike languages such as C and Java, Python variables are very flexible: they can be declared on the fly when you first use them; you can assign different data types for the same variable; and you can even name them dynamically:

for i in range(10):

exec("var_%d = %d" % (i,i))

This snip of code is the equivalent to the following:

var_0 = 0

var_1 = 1

var_2 = 2

(...)

As you can see, the variable names are created at runtime. Therefore, if you name your objects correctly in the Blender file, you can store them in variables named after them. The following code snip assigns the scene objects (retrieved from the game engine) to variables named after their names.

(...)

for object in scene.objects:

exec("%s = object" % (object.name))

Although we have flexible data types, we must respect variable types while manipulating and passing/returning them to functions. Here you can see a list of the data types you will find in the UPBGE game engine API:

Integer: This is the most common of the numerical types. It can store any number that fits in your computer memory. You can perform any regular math operations on it, such as sum, subtraction, division, modulus, and potency.

my_integer = 112358132134

Float: This type is very similar to integers, but has a range of numbers that includes fractions. If you divide an even number by its half, Python will automatically convert your integer to a float number.

simple_float = 0.5

phi = (1 + math.sqrt(5)) / 2 # ~1.618

Boolean: As simple as it sounds, this data type stores a true or a false value. It can also be understood as an integer with the value of 1 or 0.

i_am_enjoying_the_manual = True

i_am_understanding_the_manual = i_am_enjoying_the_manual - 1

List: A list contains a conjunct of elements ordered by ascending indexes. Although the size of a list can change on the fly, you can’t access a list index that wasn’t created yet (this will crash Python). List can have mixed elements such as integers, strings, and objects.

my_list = [3.14159265359, "PI", True]

Tuple: This is another kind of list where elements can’t be overwritten. As with lists, you can read them using indexes. But it’s more common to access all the values at once, assigning them to different variables.

t,u,p,l,e = (1,2,3,4,5) # works as: t = 1, u = 2, p = 3, ...

String: Whenever you need to store a text, you will use strings. As words are a combination of individual letters, a string consists of individual characters. Indeed, strings can be understood as a list of characters because you can access them using their location index, though you can’t overwrite them (like in a tuple).

python = "rulez"

Dictionary: Like a list, a dictionary can store multiple values. Unlike a list, a dictionary is not based on numerical index access. Therefore, we have strings working as “keys” to store and retrieve the individual variables. In fact, anything can be a key to a dictionary, a number, an object, a class …

_3d_software = {"name ": "UPBGE", "version": 0.3}

Custom Types: These are things such as vectors and matrixes. The game engine combines some of the basic data types to create more complex ones. They are mainly used for vectors and matrixes. That way you can interact mathematically with them in a way that basic types won’t do.

mathutils.Vector(1,0,0) * object.orientation # the result is a Matrix

Indentation

Indentation, the amount of white spaces or tabs you leave before a new line.

When coding in a particular programming language, it’s mandatory to follow its general syntax. In that regard, Python is one of the most restricted languages out there. Think of this as a tough grammar exam. You won’t be able to score high unless you follow all the pre-established grammar rules. Now imagine that it could be even worse, as bad as a written legal document. We are talking about strict paragraphs, indentation, information hierarchy, and similar rules.

As in a legal document, those rules have a raison d’etrê. With strict form/syntax, you can focus more on the content of the text. And ambiguity in the context of code making is fatal.

Indentation is the most important aspect of Python syntax. Python code uses the indentation level to define where loops, functions, and general nesting start/end. Take a look at this example:

1 def here_i_am(): # definition of the first function

2 print("I'm inside the first function.")

3 print("I'm outside the function.")

4 def but_I'm_not_here(): # definition of the second function

5 print("For you can't see me!")

6 print("I'm still outside the function.")

7 here_i_am() # calling the first function

Here we are defining a function (1–2), calling a built-in print function (3), defining another function (4–5), calling another built-in print function (6), and finally calling the first function we declared (7).

The output of such script will be:

I’m outside the function.

I’m still outside the function.

I’m inside the first function.

The first thing you may notice is that Python runs from top to bottom. Therefore, you must define your function before you call it. Secondly, you can see that the second function is never called. So how can the code interpreter determine which print statements to call? The answer is: indentation! Whenever you change the indentation level (lines 1–2, 2–3, 4–5, and 5–6), you determine the hierarchical relation between the elements. Therefore line 2 belongs to the function defined in line 1, line 5 to line 4, and the other lines are all at the same level.

Python pep-8 standard recommends to use spaces for identation. In the manual we will use 2 spaces identation.

Note

Pound Sign, I (Finally) Love You

If, like me, you never understood the reason for the number/pound sign key (#) on your phone, you will eventually find it very useful. In Python, any text to the right of a pound sign is ignored by the interpreter. Therefore, the pound sign is used to add commentaries to your code or to temporarily deactivate part of it.

OOP - Object-Oriented Programming

Since games deal with 3D world objects, it makes sense to use a language that is oriented to them. The game engine itself is written in C++, a very strong and object-oriented language, and Python OOP capabilities let you handle the game data in a Python-native way. It reflects in the game engine objects having their own set of functions and variables directly accessed from a Python API (to be explained later in this chapter in the section “Using the Game Engine API - Application Programming Interface”).

In the Python code, you can (and will) create your own classes, modules, and elements. For example, you may want to control some 3D elements as a group defined by your code. It will make it easy to get to all of them at once. Therefore, you can have a custom class that will store all the related objects you want to access and preserve some properties as a group.

Download the example 002_oop.zip, extract it and load the oop.blend file.

The first script that runs in this file is the init_world.py. Here we are creating two groups to store different kind of elements (cube and sphere). In order to sort the objects between the groups, we go over the entire scene object list and check for objects with a property “cube” or “sphere” and append them to their respective lists.

# ################ #

# init\_world.py #

# ################ #

import bge

from bge import logic as G

from bge import render as R

# showing the mouse cursor

R.showMouse(True)

# storing the current scene in a variable

scene = G.getCurrentScene()

# define a class to store all group elements and the click object

class Group():

def __init__(self, name):

self.name = name

self.click = None

self.objects = []

# create new element groups

cube_group = Group("cubes")

sphere_group = Group("sphere")

# add all objects with an "ui" property to the created element

for obj in scene.objects:

if "cube" in obj:

cube_group.objects.append(obj)

elif "sphere" in obj:

sphere_group.objects.append(obj)

elif "click" in obj:

exec("%s\_group.click = obj" % (obj["click"]))

G.groups = {"cube":cube_group, "sphere":sphere_group}

After storing them in the global module bge.logic, we wait for the user to click in the cube or sphere in the middle of the scene. When that happens, it will toggle the value of the on/off property of the cube or sphere. The following script (which runs every frame) will then hide/unhide the group’s objects accordingly.

# #################### #

# visibility\_check.py #

# #################### #

from bge import logic

# defines a function to hide/turn visible all the objects passed as argument

def change_visibility(objects, on_off):

for obj in objects:

obj.visible = on_off

# retrieve the stored groups to local variables

cube_group = logic.groups["cube"]

sphere_group = logic.groups["sphere"]

# read the current value of the "on\_off" property in the cube/sphere

cube_visible = cube_group.click["on\_off"]

sphere_visible = sphere_group.click["on\_off"]

# calls the function into the group object with the visibility flag

change_visibility(cube_group.objects, cube_visible)

change_visibility(sphere_group.objects, sphere_visible)

And we are done with this interaction. Play with the file by adding new elements (tubes, planes, monkeys) and make them interact as we have here. A few copies and pastes should be enough to adapt this code to your new situation. Remember to note the current indentation used.

Where to Learn Python

If you have previous experience with another programming language, you will learn Python in no time. If you go over some basic Python tutorials, look at some script examples, and check the UPBGE game engine API, that might be enough. But if learning Python is your first step into coding experience, don’t worry. Take the time to read through the basics of the language, start with the simplest tasks, and never give up.

Usually, a good way to start is tweaking ready-to-use scripts, which doesn’t require you to understand all the aspects of the language before your first experiments. Also, it gives you a good motivational boost by producing quick results for your efforts. We recommend you first learn Python and then focus on its application in the game engine. But you may be more comfortable messing with game engine files first and then later learning Python more deeply.

Online Material

Below are some websites where you can learn more about Python.

http://www.python.org/ and https://docs.python.org/3/tutorial/index.html

Learn about new Python versions, API changes, and module documentation.

https://upbge.org/docs/latest/api/

Official Blender + UPBGE API Documentation, all the built-in modules that can be used with the game engine.

Blender Artists forum, you can find good script examples in the Python section (general Blender Python) and in the game engine section.

http://www.diveintopython3.net

Dive Into Python 3 covers Python 3 and its differences from Python 2. A complete book available online.

This interactive tutorial website offers a great introduction to Python for beginners.

Offline Material

Books, there are plenty of them in your nearby library.

Python Built-in Help

You can also access help directly in Python.

dir(python_object)

The Python function “dir” creates a list with all the functions/modules/attributes available to be accessed from this object.

help(python_function)